The Potential Impact of CECL

Lending and the Economy

While not its direct intent, the new current expected credit loss (CECL) standard could have a significant impact on the lending decisions of affected institutions. If firms need to reserve for losses earlier than they do now – even if the total amount of reserves were to remain unchanged – the change in timing alone could potentially lead to higher funding costs, which could ultimately get passed on to borrowers. We consider three major channels for CECL to impact consumer lending and the broader economy:

- Product offerings: Will CECL affect the products lenders offer? Will credit availability be reduced?

- Consistency in loss reserving and risk management across bank and nonbank lenders: Will CECL level the playing field across lenders? Will nonbanks be impacted more than regulated banks?

- Business cycle dynamics: Will CECL act as a countercyclical weight on lending standards? Or, will CECL be even more pro-cyclical than the current system?

A Bumpy Road Ahead

While the implementation of CECL has the potential to provide investors with better information and strengthen the financial system, there are many details that will need to be worked out. How regulators will adjust capital calculations to account for CECL is a large unknown that could have large ramifications on the cost and availability of credit. But the size of the task and chance of imperfection should not overshadow the benefits a more forward-looking system will bring. Just as occurred with the implementation of stress testing, CECL’s adoption is likely to be bumpy.

It will take several years for lenders’ systems to mature and for auditors and regulators to agree on best practices.

The transition won’t be costless, but when implemented correctly it should ultimately result in a stronger financial system that serves not only lenders and their shareholders, but borrowers as well.

Product Offerings

Will we see shorter loan terms? Moving from an incurred loss model with a relatively short loss emergence period to a lifetime loss model will have the greatest impact on longer term loans. In particular, mortgage and student loans with contractual terms of 10, 15 or even 30 years will see a significant increase in their loss reserve estimates as compared to short-term personal loans or commercial loans with typical terms of just a few years.

Loans with extremely short terms could experience no change in their reserve estimates and could actually see them decline in some instances. Loss estimates under CECL should account for early payoffs, so the effective term for a 30-year fixed rate mortgage may be closer to 7 or 10 years given the tendency of borrowers to move or refinance their loans. While this helps to decrease the time of exposure, the difference from the current system, which may focus on a loss emergence period of a year or two, is substantial. Considering loan term in isolation, CECL would be expected to cause lenders to favor shorter term loans and increase the interest rate spread on longer term loans to cover their higher allowance expense. Similarly, the cost for higher risk loans to subprime borrowers may rise since the likelihood of default is greater than for prime borrowers.

As a result, lenders may need to set aside more money for this transaction with respect to the CECL standard.

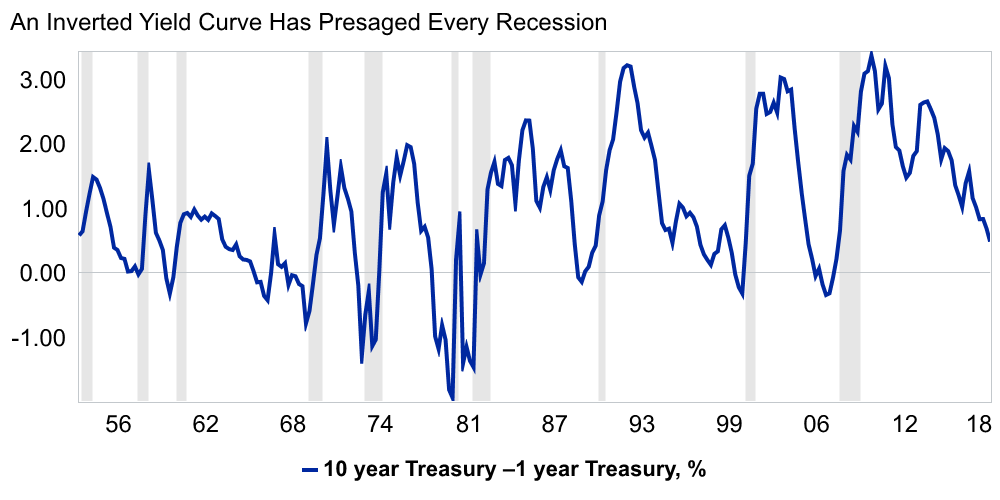

Credit availability may be reduced as a result. From the standpoint of the overall financial system, loans with shorter loan terms could provide a better match with the liabilities on lenders’ balance sheets, thereby making the financial system stronger and more resilient to changes in interest rates. Notably, many previous recessions have either been caused by or aggravated by banks’ struggles to remain profitable or solvent when their short-term funding rates rise above their long-term lending rates. The inversion of the yield curve has presaged every recession since 1950 in part because of the strain it puts on the banking system.

Sources: Treasury, Moody’s Analytics

The flipside of reducing the risk for banks is that borrowers may bear more of the interest rate risk. For example, borrowers may be incentivized to take out shorter term mortgages that they will need to refinance periodically as is done in Canada. Or, they may need to pay a somewhat higher interest rate for the peace of mind of locking it in for 30 years.

Ultimately, CECL’s impact on the products that lenders offer will depend on how it is implemented and how borrowers and financial markets react and adjust to the changes. If CECL results in less uncertainty or lowers the probability that a lender will become insolvent, then the lender may benefit from lower funding costs that offset the increased cost of reserving for losses earlier. While the lifetime aspect of CECL may favor shorter term loans, the impact is likely to be small once all of the costs and benefits are accounted for. Government support of the residential mortgage and student loan markets will insure that longer terms loans will continue to be available to borrowers.

Consistency in Loss Reserving and Risk Management

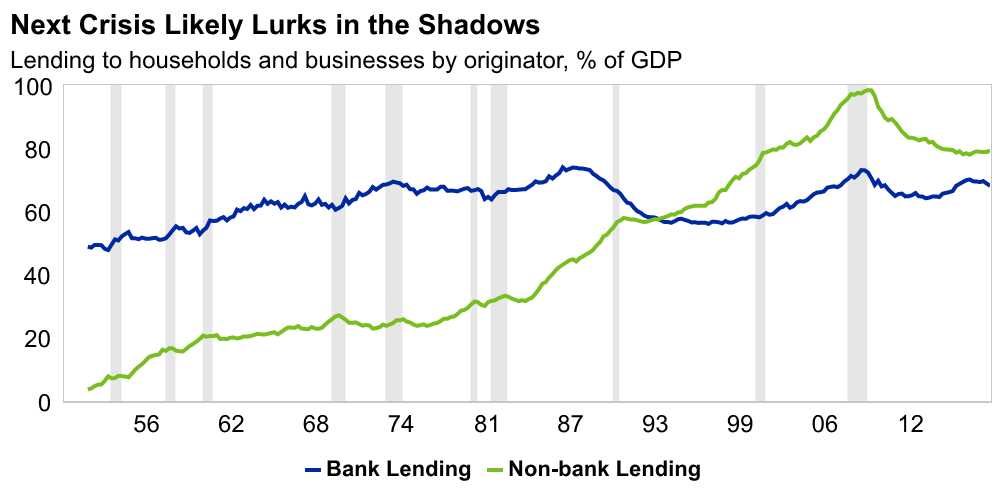

Could non-banks lose an edge? CECL could potentially impact the financial system by leveling the playing field between bank and non-bank lenders. As indicated in the chart below, the portfolios of lending institutions that are not directly regulated by agencies overseeing banks or credit unions have grown significantly in the wake of the recession, raising concerns around systemic risk.

During the last recession, regulators were able to intervene quickly and provide support given that most of the credit was provided by regulated financial institutions. With non-banks expanding into the mortgage origination market and fintechs and other non-bank lenders providing an increasing number of consumer loans, a large share of household credit is now outside of regulators’ reach. The chances of system-wide failure during a crisis are higher as a result.

Sources: Federal Reserve,

Moody’s Analytics

Sources: Federal Reserve,

Moody’s Analytics

The financial crisis resulted in an increase in the capital requirements facing regulated banks and credit unions. The Dodd-Frank Act stress testing program and the Federal Reserve’s annual Comprehensive Capital Analysis Review (CCAR) process forced the largest banks and credit unions in the country to run detailed analyses of their credit loss positions and gave the Federal Reserve the power to withhold dividend payments to bank shareholders. While institutions decried the increased regulatory burden, these exercises were instrumental in restoring confidence in the banking system. U.S. banks now command a premium position in the world and are enjoying record profits – partly due to the increased strength of their balance sheets.

At the same time, these regulatory burdens created an opportunity for non-bank institutions to expand into markets, such as personal loans and mortgages. While benefitting consumers, these non-bank lenders may have introduced additional risk into the system.

With fewer publicly available financial disclosures and limited regulatory oversight, it is difficult to judge the size and scope of non-bank lending overall. As CECL will apply to all types of institutions, it should allow for greater comparability of loss estimates across the lending industry. Forcing all lending institutions to set aside loss reserves at origination should lead to more prudent – and more consistent – risk management across both banks and non-banks.

To the extent CECL reveals any underpricing or overly optimistic assessments of credit quality among particular lenders, it could lead to higher interest rates for certain products and a reduction in available credit. While contractionary in the short term, a more level playing field would reduce the amount of risk in the financial system as a whole.

While different from IFRS9 in some key respects, CECL should make international comparisons easier as loss reserve standards can vary by geographic jurisdiction. Greater transparency across the globe should result in a more efficient allocation of capital and reduce some of the risk of another international financial crisis. CECL’s disclosure requirements will shed more light on the lending standards and portfolios of non-bank lenders. More direct comparisons will allow investors to better assess risks and impose consistency across lenders.

Consumer Lending

The greatest promise of CECL from a broader economic standpoint is the potential for it to act as a countercyclical weight in the credit cycle. Ideally, imposing greater recognition of losses earlier in the lending and servicing process should reduce the chance that lending standards loosen too much too quickly as occurred during the housing boom of the last decade. To illustrate CECL’s potential impact, consider the credit cycle characterized by four phases:

- Expansion – wherein outstanding balances rise along with delinquency rates

- Slowing – wherein balances contract as lenders start to pull back, but delinquency rates rise

- Contraction – wherein outstanding balances contract with delinquency rates

- Acceleration – wherein balances rise as lenders start to loosen, but delinquency rates remain low

4 Phases of the Credit Cycle for Auto Loans and Leases

Sources: Equifax, Moody’s Analytics

The credit cycle itself is a result of the lagged nature between credit decisions and observed outcomes. That is, when a lender originates a loan and the borrower starts to pay, it may take years for the lender to observe whether the borrower pays back the debt or defaults. As a result, it may be difficult for individual lenders to incorporate broader trends in the credit cycle into their individual lending decisions in real time. When times are good, lenders will be under pressure to increase volume and market-share. Conversely when times are bad, shareholders will demand conservatism.

CECL offers a mechanism for formally incorporating this dynamic directly into the loss reserving process such that it acts as a countercyclical signal. In addition to reflecting the portfolio composition, expected loss estimates should rise as the probability of a correction or economic recession increases.

For example, if house prices historically have grown at 3% per year but are suddenly growing at 10% per year, the likelihood of a correction or a return to long run trend should be higher. The higher loss reserves required as a result should lead lenders to tighten up their lending standards. CECL’s shift in timing should force lenders to deal with the possibility of higher losses when they are best positioned to prevent them – at loan origination.

In theory, CECL sounds wonderful and eventually it should be. However, as discussed in Part 2 of our series “Getting to Know CECL,” the outcome of CECL on individual lenders and the economy more broadly depends heavily on the underlying assumptions lenders will use in their calculations.

CECL’s principles-based approach offers tremendous flexibility, but also runs the risk that firms will not interpret the rules in a manner that benefits the overall system. Take the use of forward-looking economic scenarios. Lenders could take the approach of using a benign, single “most-likely” scenario based on consensus views of where the economy is headed over the next year or two. Such an approach may meet a strict interpretation of being “reasonable and supportable,” but falls short of a more realistic view that should consider the possibility that the economy could fall into recession. Recognizing this, auditors, regulators and investors will be paying close attention to the economic forecast assumptions behind an institution’s CECL estimates.

Overly optimistic views will be much easier to spot given CECL’s disclosure requirements. As a countercyclical weight that encourages lenders to increase their loss reserves in good times, CECL holds tremendous promise over the current system. However, there is a risk that lenders will not consider a spectrum of potential outcomes when setting their forward-looking reserves.

At worst, lenders could take a naïve, short-sighted view and forecast the future based on recent history – similar to the existing incurred loss model.

Knowing this, auditors and regulators will require more holistic views of losses, thereby preserving CECL’s countercyclical qualities. For more information on how we can help your financial institution prepare for CECL, call your Equifax account representative, or contact us today. Additional resources can also be found on Equifax and Moody’s Analytics websites.

Recommended for you